Canberra Women in World War I: Community at Home, Nurses Abroad

When World War I began Canberra was officially just over one year old. It had barely begun to change from the scattered farming community it had been before it was chosen as the site of the National Capital. In 1914 its population was less than 2,000 [1] including some recent arrivals employed on the initial works in the building and administration of the new city. [2] Construction was well under way in 1914 but ceased almost entirely by the third year of the war. Queanbeyan over the border in New South Wales remained the town centre for residents of the Federal Capital Territory (not named Australian Capital Territory until 1938), as it had been for the European settlers and convicts on the Limestone Plains from 1838 when it was declared a township.

The majority of the adult female population consisted of wives and mothers involved in home duties and single women employed in a few occupations particularly nursing, teaching and domestic work. The Canberra men who enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) give some indication of the range of the male population during the World War I. They were farmers' sons, labourers from the construction sites, clerks from the Federal Capital Territory administration, workers from the major properties and from small communities such as Hall and Tharwa, cadets rushed through their accelerated officer training courses at the Royal Military College (RMC), Duntroon, and College staff. Members of local grazier families and prominent citizens enlisted, including Andrew Cunningham from Lanyon who won the Military Cross (MC) in 1917 and the Rector of St John's Anglican Church, Reverend Frederick Greenfield Ward, who served as a chaplain and was awarded an MC in 1918. [3] Selwyn Miller, son of the Territory Administrator Colonel David Miller and his wife Jane Miller (nee Thompson), served with the British Army. Many workers such as Clyde Hollingsworth, a blacksmith from Hall, who was killed in action on the Western Front in 1917, enlisted in the AIF. [4]

The nurses who enlisted to serve overseas in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), all single women pursuing careers, represented a small strand of the female population. They included three members of the Gallagher family who were born in what became the Federal Capital Territory, six who came to Canberra to nurse either at the military hospital at Duntroon or at Canberra Hospital and three who had family associations. Among them were Patricia Blundell who came from Melbourne to nurse at Duntroon and Gladys Boon and Amy Bembrick who were descendants of the pioneer Southwell family. [5]

Many of the first nurses to leave for the war were sent to Egypt where their first patients were from Gallipoli.

The role of women in the war effort at home was dictated by their place in society in an era in which women were rarely visible in the historical record. Much of the information about women in the Canberra community at this time is available only through their husbands' records and history. In 1914 women were overwhelmingly wives and mothers caring for families in homes with few labour-saving devices. In the Canberra region most of the population lived in rural settings, in small villages such as Hall in the north of the Territory or Tharwa in the south, in small settlements such as Ainslie close to what was planned as the city centre, or on farms that were some distance from neighbours and social centres. Those with men at the front faced constant anxiety and terrible grief and trauma if loved ones were killed, wounded or missing. Christina Campbell, whose family lived at Yarralumla until it was acquired by the Commonwealth in 1914, later to become the Governor-General's residence, refused to accept that her son Charles was dead after he was reported missing in action in France on 29 November 1917. She travelled to Egypt to be near her other son, Walter, serving in Palestine, then after the war went to Europe in an attempt to trace her missing son and she persuaded her husband to allocate a considerable sum in his will for the missing son should he ever return. [6] Mrs Ellen Clark, the teacher at Weetangera School, cried with joy when she heard the war was over and her son Kenneth Arthur Clark DCM, a sergeant in the 59th Battalion, would be coming home safe. She called an assembly and told the children they could have the day off. [7]

Canberra had no town centre or local newspaper - the nearest commercial centre was Queanbeyan and the Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer (Queanbeyan Age before 1915) was the chief news source for the region. Many wartime activities were channelled through organisations in Queanbeyan and the village of Hall, where there were well-established social, church and community links, but within the Territory women responded to the war with patriotic fervour, setting up new networks in a society in transition.

Within days of war breaking out the Governor-General's wife, Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, appealed by letter and through newspapers for support from the wives of state governors and Territory administrators. It is unclear whether she included the new Federal Capital Territory in her appeal. Historian Ernest Scott mentions only that she 'set the machinery in motion for organising red cross societies in every State, as well as in the Northern Territory and Norfolk Island'. [8] Possibly she overlooked the new Capital Territory because of its small size and newness. Nevertheless, the Territory Administrator's wife Jane Miller invited women from prominent families to a meeting in the Residence at which she asked their support in initiating a movement to assist soldiers and sailors on active service and their families and the French and Belgians suffering in the face of the German advance. Supported by Ida Parnell, wife of the commandant of RMC Duntroon, she proposed a division of districts each with a representative who would appeal for funds and distribute collecting boxes. The committee elected at the meeting, representing a synthesis of the old pastoral families, the new public servants and the RMC community, comprised Jane Miller as president, Nina Macartney and Jessie Barnard from Duntroon, Blanche Crace from the pastoral property 'Gunghaleen' in the Ginninderra area in the north of the Territory, and Catherine Sheaffe, wife of senior surveyor Percy Sheaffe, from Tharwa. [9]

In the Territory's south, grazier's wife Mary Cunningham of Lanyon raised funds for the Red Cross by holding balls and fairs. Later in the war she was President of the War Chest Flower Shop in Sydney, and she worried about family members serving overseas. Her son Andrew served with the Light Horse, her sisters Joan and Phoebe were overseas, one as a nurse the other with the Red Cross, and two of her daughters lived in Egypt then in London where Mary Paule was with the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and 'Tommy' drove ambulances and visited wounded soldiers in military hospitals. [10]

Miles Franklin. Courtesy John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The famous Australian writer Miles Franklin who spent her childhood at Brindabella, later close to the New South Wales border with the Federal Capital Territory, also served as a volunteer in World War I. After living in the United States she volunteered in England and was attached to the American unit of the Scottish Women's Hospitals which was stationed at Ostrovo in Macedonia. She worked as a nursing orderly tending Serbian casualties from the Serbian/Bulgarian conflict while over the border at Salonika in northern Greece, Australian Army nurses including four with connections to Canberra served in British military hospitals tending casualties from the same conflict. Miles Franklin, like many members of the AANS, caught malaria and had to return to London in February 1918 after six months' service. [11] Some Australian army nurses had to be repatriated to Australia including one of the twelve nurses connected to Canberra, Ruth Steel, who had recurrent bouts of malaria.

Women the length and breadth of the Territory supported the war effort by forming local branches of the Red Cross, the War Comforts Fund and fundraising for the various patriotic societies. They prepared food parcels, knitted socks, balaclavas and scarves, sewed pyjamas, wrote letters to the men overseas, supported each other when their sons or brothers or husbands or friends fought on the battlefronts and comforted each other as best they could when family or friends appeared on the casualty lists. In the Ginninderra area, Blanche Crace introduced weekly knitting classes to encourage more women to knit socks for the men in the trenches.

The women's contributions were not made easily. Distances were far and could often only be travelled by horse and buggy or on foot. Few had access to motor transport apart from women from wealthy grazier families such as Mary Cunningham. Most of the women about whom there are sources enjoyed the luxury of staff who ran their homes and cared for their children, freeing them for the war work. For others it might not have been so easy but there is only fragmentary evidence of these women in the record. In Hall, widowed Susan Hollingsworth cared for three children and six grandchildren and endured the loss of her son, Clyde, on the Western Front. Still, she made time to support the local Red Cross and the minutes of the Yass Red Cross committee note her presence at many of the organisation's fundraising events around the district. Within a month of the establishment of the Ginninderra Red Cross branch, the women had produced 24 pairs of pyjamas, 36 flannel shirts, 36 vests, 24 handkerchiefs and numerous pairs of socks for the soldiers overseas. The various local groups held balls, fairs, sports days and concerts to raise funds and morale. By August 1915 the Territory's War Food Fund had raised £1531/17/5 (about $150,000 in today's equivalent). [12]

While most of the women who appear on the historical record were the wives of prominent citizens and were not in paid employment, one woman in particular stood out as different. Hilda McIntosh took over the role of Canberra postmistress in early 1913 and continued in the role well beyond the end of World War I, managing the collection and delivery of letters and telegrams, including the dreaded pink telegrams advising of the death or injury of a loved one.

Sources about women during this period are scant. Details are found through the records of eminent husbands, or through news reports of fundraising events when the women are referred to by their husband's initials. While it is easy to identify Mrs J. Parnell or Mrs D. Miller and Mrs E.G. Crace, a number of women with the name Brown in the Hall area are not easy to identify. For Mary Cunningham of Lanyon, additional sources include an archive of family letters in the National Library of Australia as well as her biography by Jennifer Horsfield. Both these sources reveal her involvement in the Referendum Reinforcements Campaign Committee as a strident supporter of the Yes vote in the conscription campaigns.

Conscription

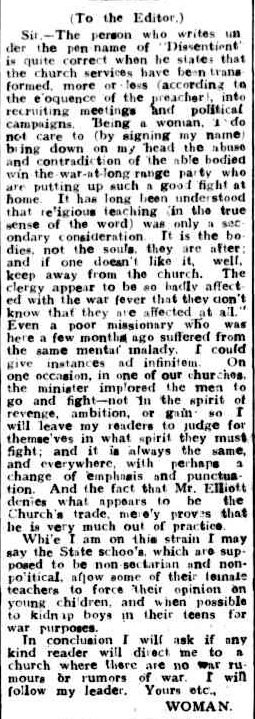

The involvement of women in anti-conscription and anti-war causes is more difficult to document than their work for patriotic causes, their support for conscription and their enlistment as nurses, but it seems likely that local women would have been involved in this politically and socially divisive campaign. Differences of opinion on conscription caused strife in church communities. In 1918 a correspondent in the Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer, who signed herself 'Woman', complained that church services had been transformed into recruiting meetings and political campaigns. She added that the clergy appeared so badly affected with war fever that they were unaware they had been 'affected at all'. [13]

Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer , 5 February 1918, p. 2.

Although the conscription vote was balanced almost equally in Canberra, the city was in a district that was strongly against conscription and voted about two to one against, even more strongly in some country areas. In the first conscription referendum in 1916 Canberra voted 612 to 590 against conscription, in Queanbeyan the vote was 693 'No' to 356 'Yes'. [14] In the second referendum in December 1917 Canberra voted for conscription by a majority of 6 votes but in the surrounding district the 'No' vote was stronger than in 1916. In the small settlement of Michelago the vote was nine to one against, [15] yet the memory now of Michelago in World War I is more likely to be of Michelago-born Brigadier General Granville Ryrie and the book My Darling Mick based on his letters to his wife. [16]

Newspaper reports describe male speakers at anti-conscription meetings at the Powerhouse and brickworks in Canberra, whereas in nearby Queanbeyan women spoke for and against conscription. On 24 October 1916 the Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer reported that Florence Fourdrinier had recently addressed a meeting at the Triumph Hall in support of conscription and noted that a number of women kept up a stream of interjections despite the chairman's appeals for order. [17] Fourdrinier became a close friend of Mary Cunningham when they worked together on the War Chest Flower Shop in Sydney. A photograph of Mary shows her in a motor car with others on the conscription campaign. [18]

Mary Emily Cunningham on the pro-conscription Referendum Reinforcements campaign (which woman she is is unknown), c.1917. Courtesy Lanyon Homestead, ACT Museums and Galleries.

While there is no mention of Canberra women involved in the anti-conscription campaign, it is possible some of them attended meetings in Queanbeyan and Hall. During the second referendum campaign the Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer reported that Mrs Jennie Scott Griffiths addressed an anti-conscription afternoon meeting of women at the Triumph Hall on 20 November 1917. That evening she and Mr Cecil Whitmore put the case against conscription to a crowded house at Hall. [19] Griffiths also spoke at Michelago, Williamsdale and Bungendore. A prominent feminist, pacifist and socialist, American-born Griffiths (1875-1951) was the editor of the Australian Woman's Weekly (published from 1912 to 1921) before her employers sacked her in 1916 for opposing conscription. [20] A mother of ten children, noted for her small stature, American accent and passionate conviction, Griffiths was a colleague of political and social activist Kate Dwyer on the Women's Anti-Conscription Committee and served with Vida Goldstein in the Women's Peace Army. Whether or not Canberra women heard her radical views, she is sure to have been a talking point.

Queanbeyan nurse Mary O'Rourke recorded in her diary on 19 December 1917 that she had attended an anti-conscription meeting: 'Went over the street to the Anti meeting'. After the vote she wrote, 'The majority is for No up to the present, No in nearly all the States is leading'. [21] The Australia-wide verdict in both referendums was against conscription.

Aboriginal women

One group of women noticeably missing from the story of Canberra women during World War I are the local Ngunnawal Aboriginal people who had lived in the region for 25,000 years but were displaced from the 1820s when European settlers began arriving. In 1911 when Canberra was established as the new national capital, the NSW Aborigines' Protection Board forced all Aboriginal people in the new Territory to the Edgerton Mission Station at Yass. [22] After the mission closed in 1913 they lived on the outskirts of Yass. Among the women were those whose sons or husbands served with the AIF including Johanna Lewis (nee Walker) who married in Yass and saw her husband William James Lewis and 21-year-old son Thomas Amos enlist together in 1915. Her husband returned; her son was killed in July 1916 at Pozieres on the Western Front. Initially reported missing in action, it was more than a year before Johanna and Tom's sisters Gertrude and Nellie knew his fate.

In Sydney Annie Elizabeth Brown (nee Shea) and her daughters feared for their son and brother Samuel Protest Brown, born at Pudman Creek near Boorowa close to Yass, who enlisted at the start of the war and served throughout. His army file does not record the fact that he was Aboriginal but he came from a family recognised by the present day Ngunnawal people. [23] A farrier by trade, he served with the 2nd Light Horse Ambulance at Gallipoli then in Egypt until his return to Australia at the end of the war. [24]

There is more to be told about the lives of Aboriginal women in or connected to the district during World War I. Possible significant sources have been located as the project nears completion but timeframes do not permit further development of this aspect of Territory life at this time. It is hoped, however, that it will be subject of further research and another project in the near future.

Enemy aliens at the Molonglo Concentration Camp

While the women of the Canberra region feared for or grieved for their loved ones on the battlefront, later in the war another group appeared in the Territory against their will. In August 1918 two hundred women, men and children of German origin or connection arrived at Queanbeyan by train and were marched to the Molonglo Concentration Camp where they were held until May 1919. Their arrival aroused local interest. Mary O'Rourke noted in her diary on 27 May 1918 that the first one hundred internees had arrived and that 'quite a lot of people went up the railway to see them'. [25] Among the internees were Ellen Rohrmann, Klara Kutsche and Luise Hurtzig with her husband and two young daughters, along with three unnamed young Austrian women who feature in photographs on the Australian War Memorial website. Ellen was to die at the Molonglo Camp - of sunstroke and complications - and never see her home again.

Three Austrian girls with a cart waiting for their ration allowance at the German Molonglo internment camp, c.1918. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Extraordinarily, among the group of 200 prisoners were two Australian-born sisters who were married to German cousins. Daisy Schoeffel with her husband and two babies and Hally Kienzle with her four stepchildren had been forcibly evicted from their homes in Fiji, their property liquidated, and shipped by steerage to Australia where they were first held in the camp at Bourke before being moved to Molonglo. After the war Daisy wrote to a Member of Parliament telling him of the appalling treatment and the physical and mental hardship of their imprisonment. But, she added: 'what hurt us more than all the insults and hardships we were forced to endure during our 2 years internment, was the fact that we should have to suffer all this at the hands of our own men and in our country!' [26]

Luise Hurtzig kept a diary from which we know that, like the Canberra women, she lived with anxiety for her family and friends fighting at the battlefront. She also feared for the impact of his imprisonment on her husband and worried about her eldest daughter back at home in Germany with her grandparents. Luise's husband was a sea captain and she and her two younger daughters, Hanna aged 5 and Lore aged 2, had joined him for an adventure leaving 9-year-old Eva at home so she could attend school. The family had the misfortune to be in Brisbane harbour when war broke out. The Hurtzigs were seized and interned in Enoggera and Berrima Concentration Camps before they were transferred to Molonglo. It was to be five years before they saw their eldest daughter again.

The World War I experiences of all these women are more fully documented in individual entries in Community at Home.

Army Nurses with connections to Canberra

Twelve nurses with some connection to Canberra served overseas with the AANS in World War I. The service of women who served overseas as nurses is easy to find compared with the involvement of women in home front activities, particularly since the digitisation of personnel records and, in the case of nurses with a Canberra connection, research undertaken by Canberra & District Historical Society member, Michael Hall, for the ACT Memorial. The nurses' war records include their births, ages, religion, physical characteristics and details of where they served, the hospitals where they nursed, their illnesses, their discharge and repatriation and the medals they were awarded. [27]

Other details of their lives, however, such as their family circumstances, where they trained, their careers in nursing before and after the war, their marriages and their deaths can be just as difficult to trace as it is for civilian women because of their absence from historical records, although in a few cases their war service made them more newsworthy. Evelyn Gallagher's nursing career from her Army discharge in 1919 to her death in 1946 was very difficult to trace even with the help of Neville Gallagher, the author of a book about the Gallagher family. [28] Eventually with the help of the Shoalhaven Historical Society it was possible to establish that she had been matron of a private hospital in Nowra NSW until shortly before her death although details still remain sketchy. Similar problems remain with some other nurses including Evelyn's niece, Janet Gallagher, whose subsequent career in nursing has not been traced in detail.

The twelve Canberra nurses represented a more diverse cross-section of the nursing profession in Australia at that time than the more homogenous groups who enlisted from a particular country town or district or a city suburb. Older than the average age of nurses who enlisted and more mobile, they came from far-flung places, country and city, from Australia and England and from a range of backgrounds and social strata. Some had trained in large well-known city hospitals, others in small bush or suburban cottage hospitals. Of the twelve, three were born in what became the Federal Capital Territory: two Gallagher sisters, Flora and Evelyn, and their niece Janet Gallagher, born at Browns Flat near Burbong in an area now known as Kowen Forest on the eastern edge of the Territory. At the time they were born, it was a farming community about mid-way between Queanbeyan and Bungendore. All trained at hospitals in Sydney before enlisting.

Four of the twelve nursed at Duntroon Military College Hospital which had begun in 1912 partly in tents. By 1914 it was permanently housed and nursing sisters had begun to take the place of male medical orderlies. Those who nursed at Duntroon were Madeline Patricia Blundell and Frances Alice Robinson who came from Victoria and Marie Whitlock and Alma McKnight who came from country districts of New South Wales. Two nurses, both British-born, were employed at Canberra Hospital which opened in 1914 as an eight-bed centre to treat employees of the Department of Home Affairs engaged on building Canberra. Gertrude Lawlor was matron at the hospital both before and after her war service; Ethel Macfie nursed at the hospital for a short time. The remaining three nurses had family connections: Ruth Steel through her father, Rev. Robert Steel, Presbyterian minister at Queanbeyan whose parish took in what became the Territory, while Gladys Boon and Amy Bembrick were descendants of pioneer Thomas Southwell of Parkwood in the north-western part of the Territory.

Apart from the three Gallaghers, five of the twelve nurses were born in New South Wales, two in Victoria and two in England. Five of the nurses stated their religion as Church of England, four Catholic, two Methodist and one Presbyterian. Only three were under 30 at the time they enlisted and two were 40 or over although they gave younger ages presumably because nurses over 40 were rarely accepted for service in the AANS. [29] All were single, a requirement for enlisting. About half appear to have remained single after the war but among the younger nurses there were two wartime romances and post-war weddings. Marie Whitlock married an AIF officer, Major Alan Wendt, whom she met on the ship while returning from Egypt in 1919. Their wedding took place in Adelaide soon after they arrived back in Australia. In 1923 Amy Bembrick travelled to England to marry a former British soldier, Corporal Bill Gumbley, whom she met while nursing in Salonika during the war. Her husband became an Anglican Minister and they spent their lives in Anglican parishes in Australia.

Nurses in the Australian Army

Australian Army nurses in World War I did not hold military rank and were not given enlistment numbers but they were treated as officers. All staff nurses were addressed as Sister but were paid only the equivalent of a male private's pay. The salary of a matron-in chief was equivalent only to a lieutenant's. [30] Several of the nurses connected to Canberra were promoted from the usual rank of Staff Nurse to Sister and one to Charge Sister but some of these promotions were temporary and they reverted to their substantive rank before discharge. [31]

Throughout Australia there were more trained nurses willing to enlist than were needed for overseas service. In reply to newspaper advertisements late in 1916, 659 trained nurses registered that they were ready to volunteer for duty overseas. This was over and above the number needed to staff army hospitals in Australia. When the results of this survey became known in Britain, there was an immediate call for Australian nurses to staff four British hospitals in Salonika. [32] It also probably accounts for some nurses deciding to work at Duntroon which enabled them to gain military experience and to demonstrate their commitment to service which might lead to enhanced enlistment prospects. Some also worked at other military hospitals particularly Randwick military hospital. The call for nurses to work in British military hospitals in India and later in Salonika opened the way to enlistment for nurses who hoped that, after a short time, they would be moved to hospitals on the Western Front or at least to England to nurse AIF wounded and sick.

Medical and nursing sisters of 3rd Australian General Hospital, Lemnos, Greece. Patricia Blundell was in the first group of nurses to arrive at Lemnos with 3AGH.

The TV series Anzac Girls and books published to commemorate the centenary of the Great War give the impression that Australian nurses served almost exclusively at the major sites of Lemnos (Gallipoli casualties), Egypt (Gallipoli and Light Horse casualties) and the Western Front (casualties from the Somme and Flanders battlefields), and that their patients were mainly Australian soldiers. In fact their service was much more widespread. Three of the twelve nurses with connections to Canberra spent most or all of their war service in India and four served in Salonika until after the war ended. The problems they faced are rarely written about or dramatised in detail. In both places they served in British-run hospitals and their patients were not 'our boys' whom they preferred to nurse. They faced extreme weather conditions, unusual hazards and threats to their own health, yet received little of the recognition of the nurses at Gallipoli and the Western Front. In their rush to respond to British requests for nurses to help staff British hospitals, the Australian Government did not insist, or even apparently suggest, that Australian nurses should be given the opportunity to nurse in Australian-run hospitals.

Staff at Freeman Thomas Hospital, Bombay, during World War I, 1918. Evelyn Gallagher and her niece Janet Gallagher from Canberra nursed at the hospital during their postings to India during World War I.

In India their first patients were casualties and prisoners from Mesopotamia but later in the war were more likely to be troops from the Indian Garrison suffering from tropical diseases unfamiliar to the nurses. Two Australian nurses died of cholera in India. The nurses were not paid in accordance with the Australian Army pay regime, they often nursed in primitive conditions in intense tropical heat and inevitably they encountered language differences with Indian staff. [33] Moreover nurses who served only in India were not regarded as serving in a theatre of war and were entitled only to the British War Medal not the Victory Medal although there appear to have been some contradictory decisions on this matter. [34] In Salonika some patients were from the Balkan war front but many suffered from diseases particularly malaria. The weather varied from moist heat in summer to intense cold in winter and the nurses worked mostly in tent hospitals often sited near swamps that became quagmires in winter and mosquito breeding grounds in summer. Most nurses in Salonika had bouts of malaria and a considerable number had to be invalided home including Ruth Steel. [35]

Australian nurses in Salonika going on night duty dressed to ward off mosquitoes, c.1918.

Australian Army hospitals were established at Lemnos and Egypt to treat casualties from Gallipoli and in France and England to care for the huge numbers of wounded and sick from the Western Front. In these hospitals, often set up very hastily in tents, nursing was extremely demanding and stressful as casualties arrived from major battles. Patricia Blundell was among the Australian nurses who arrived at Lemnos, off the coast from Gallipoli, to find their tent hospital only partly constructed, wounded patients lying in the mud and grave shortages of medical supplies, food and even water. The nurses were housed in tents but had no beds or mattresses and they gave their eating and drinking utensils to their patients. When a further convoy of wounded arrived the nurses used their own soap and tore up items of their clothing to bandage their patients. In France, Boulonge, the site of many Allied war hospitals, became a seething mass of ambulances, wounded men, doctors and nurses. Both Flora Gallagher and Patricia Blundell spent over a year nursing at hospitals in the Boulonge area.

Many of the nurses spent some time posted to military hospitals in England where longer-term casualties were treated, often in hospitals that specialised in particular types of cases including lost limbs, shell shock, neuroses and severe illnesses. After the war ended most of the nurses still remaining in the AANS, including those from India and Salonika, were sent to England, where they nursed remaining patients and the influx from the influenza pandemic, while they waited like many thousands of AIF troops, until ships could be found for their return to Australia. Most of the nurses with connections to Canberra did not reach Australia until the latter part of 1919.

While they waited, some chose to do courses to fit them back into civilian life. Two of the twelve nurses with Canberra connections, Gladys Boon and her distant relative Amy Bembrick, studied domestic economy at the Battersea Polytechnic. Their choice fitted the prevailing post-war ideal encouraging women to give up the jobs they had done during the war and revert to domestic roles, although this attitude was not so common in relation to trained nurses. In England it was particularly evident in courses run to train women to resume domestic roles after spending the war working in munitions factories. [36]

Three of the twelve nurses with a connection to Canberra left for overseas service in 1915; two in 1916 and seven in 1917. None is known to have left letters or other material to indicate how the war affected them, for example as it affected Vera Brittain who became a leading pacifist in post-war England. It is perhaps noteworthy in this context that only a few went back to nursing after the war.

The first to leave was Patricia Blundell who embarked on RMS (Royal Mail ship) Mooltan on 16 May 1915 with 3rd Australian General Hospital (AGH). Her service was to be the most extensive and longest of all the Canberra nurses embracing nursing Gallipoli casualties in a tent hospital set up hastily on the nearby Greek island of Lemnos, then in Egypt after the hospital moved there, on a hospital ship in the Mediterranean, and at Wimereux near Boulonge nursing Western Front casualties.

Flora Gallagher and Frances Alice Robinson left on 10 November 1915 on HMAT (His Majesty's Australian Transport) Orsova with reinforcements for 2nd Australian General Hospital in Egypt. Flora Gallagher's service included nursing in Egypt and about eighteen months treating Western Front casualties at Boulonge. Robinson, after making a trip to Lemnos to evacuate patients when the hospital transferred in Egypt early in 1916, made several trips on hospital transports bringing AIF wounded and sick soldiers back to Australia. The years these long-serving nurses spent overseas affected their health and all were repatriated to Australia in the last year of the war suffering from medical conditions. [37]

Evelyn and Janet Gallagher left on 2 September 1916 on RMS Kashgar for India where they nursed in British hospitals until within a few months of the end of the war when they left to nurse in Egypt and England. During their service Evelyn Gallagher was promoted to Charge Sister, the highest nursing level recorded by any of the Canberra nurses, and Janet was promoted to Sister.

Gladys Boon, Ethel Macfie, Amy Bembrick, Ruth Steel and Marie Whitlock left on RMS Mooltan on 9 June 1917. Boon, Macfie, Steel and Bembrick served in Salonika until early in 1919 when all, apart from Steel who had been repatriated sick, were posted to England before their return to Australia. Whitlock nursed in Egypt until after the war ended as did Alma McKnight who left on 13 September 1917 on HMAT Runic but did not arrive in Egypt until nearly the end of the year after being sent via South Africa and Bombay. They were nursing in Egypt when light horse casualties arrived following the battles at Beersheba, Gaza and Jerusalem and both returned home in 1919 from Egypt. Gertrude Lawlor left for India on SS (Steam Ship) Indarra on 26 November 1917 and served only there. [38]

The detailed stories of the lives of the twelve nurses are told in individual entries in Nurses Abroad.

Conclusion

Although the new National Capital had only a small, scattered population and no established city centre during World War I, the women of Canberra made a noteworthy contribution to the war effort both within the community at home and through the service of nurses in overseas theatres of war. This is more remarkable when the disparate elements of the population are considered. The population of the Federal Capital Territory at the beginning of the war comprised three main groups: men and women who had been associated with the district before it was chosen as the National Capital, mainly farmers, rural workers, tradesmen and a few wealthy landowners and their families; the newly arrived workers, officials and office employees, teachers, nurses and domestic workers who had moved to the Capital, some accompanied by their families, to begin building and administering the new city; and the cadets, their teachers, instructors and support staff at Duntroon Military College plus some families who had arrived after the College opened in 1912.

The wartime blending of this population into an active and supportive community is apparent in the stories uncovered for this essay. Despite the well-established difficulty of researching women who lived and worked one hundred years ago because of their absence from much of the historical record, many stories of the contributions of women to the Territory's war effort at home and overseas in World War I are revealed here and in more detail in individual biographies in the Australian Women's Register, many for the first time.

DR PATRICIA CLARKE OAM FAHA and DR NIKI FRANCIS

Notes

- NAA A206, Vol. 9, 60541: FCT 1913 Census, population:1988. Return to text

- Research on FCT 1913 census and analysis of the 524 names on the ACT Memorial by Michael Hall, CDHS. Return to text

- Jim Gibbney, Canberra 1913-1957, AGPS, Canberra, 1988, p. 45. Return to text

- NAA B2455, 5827786 Clyde Hollingsworth. Return to text

- NAA B2455, 3094075 M. Patricia Blundell; 3071771 Amy Bembrick; 3098647 Gladys Boon. Return to text

- Sandy Blair et al, 'They made it: Terence Murray, Gibbes and Campbells' in Gables, Ghosts and Governors-General: The Historic House at Yarralumla, ed. Chris Coulthard-Clark, Allen & Unwin/CDHS, North Sydney, 1988, p. 42. Return to text

- Margaret Clough, Spilt Milk: A History of Weetangera School 1875-2004, Weetangera School, Canberra, 2004, p. 42. Return to text

- Ernest Scott. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. XI, Australia during the war, 4th ed., Angus & Robertson, Sydney, p. 702. Return to text

- 'Patriotic Fund Canberra', Queanbeyan Age, 25 August 1914, p. 2. Return to text

- Jennifer Horsfield, Mary Cunningham: An Australian Life, Ginninderra Press, Charnwood ACT, 2004. Return to text

- Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin, Fourth Estate, Pymble NSW, 2008, pp. 212-3. Return to text

- Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer, 24 August 1915, p. 3. Return to text

- Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer, 5 February 1918; David Stephens, 'Queanbeyan and the Great War: The Social Impact of war on a rural community', UNSW, ADFA, Department of History, 1995, pp. 57-58. Return to text

- Australia Parliamentary Papers, General Part 1, Vol. 2, 1914-17, pp. 751, 768. Return to text

- Australia Parliamentary Papers, General, Vol. 4, 1917-19, pp. 1485, 1498. Return to text

- Phoebe Vincent, My Darling Mick: The life of Granville Ryrie, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1997. Return to text

- 'The Referendum. Meetings', Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer, 24 October 1916, p. 2. Return to text

- The photograph of Mary Cunningham on the conscription campaign appears in a selection of photographs in the centre pages of Horsfield's Mary Cunningham: An Australian Life. Return to text

- 'The Referendum. Anti-Conscription Campaign', Queanbeyan Age and Queanbeyan Observer, 23 November 1917, p. 2. Return to text

- T. H. Irving, 'Scott Griffiths, Jennie (1875-1951', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra, 2002, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/scott-griffiths-jennie-11641/text20793 accessed online 15 May 2015. Return to text

- Narelle O'Rourke, A Country Nurse and Midwife: The life, career and times of Mary O'Rourke/Bowers, M.B.E. In the Queanbeyan District of New South Wales 1889-1973, N. O'Rourke, Queanbeyan NSW, 1989, p. 58. Return to text

- Australian Human Rights Commission, 'Bringing them Home' in Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Report: National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, Sydney, 1997; http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/bringing-them-home-report-1997. Return to text

- Stories of the Ngunnawal, Carl Brown, Dorothy Dickson, Loretta Halloran, Fred Monaghan, Bertha Thorpe, Agnes Shea, Sandra & Tracey Phillips, Journey of Healing, Florey ACT, 2007, p. 7. Return to text

- Private communication Tyronne Bell, Canberra, 24 July 2015; NAA B2455, 1801736 S.P. Brown. Return to text

- O'Rourke, p. 66.Return to text

- NAA CRS457, Item 406/1; Gerhard Fischer, Enemy aliens: internment and the homefront experience in Australia, 1914-1920, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia Qld, 1989. Return to text

- NAA B2455 First AIF Personnel Dossiers 1914-1920. Return to text

- Neville Gallagher, The Long Travail, N.J. Gallagher, Canberra, 1983. Return to text

- A. G. Butler, The Australian Army Medical Service in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. III, Problems and Services, AWM, Canberra, 1943. p. 543. Return to text

- Butler, Vol. III, p. 546. Return to text

- Information about individual nurses: http://nurses.ww1anzac.com; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920, NAA. Return to text

- Butler, Vol. III, pp. 541-2. Return to text

- Butler, Vol. III, pp. 567-9. Return to text

- Keast Burke, ed., With Horse and Morse in Mesopotamia: The story of the Anzacs in Asia, A. & NZ Wireless Signal Squadron History Committee, Sydney, 1927, pp 124-30 ('The Australian Nurses in India'); Bassett, Guns and Brooches: Australian Army nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 74-5. Return to text

- https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2015/01/13/mettle-and-steel-aans-salonika/; Butler, Vol. III, pp. 541-46; Bassett, pp. 84-9. Return to text

- Angela Woollacott, On Her Their Lives Depend: Munitions Workers in the Great War, University of California Press, Berkeley USA, 1994, pp. 154-5. Return to text

- NAA B2455, 3094075 Blundell; 4036498 Flora Gallagher; 1903555, Robinson. Return to text

- https://www.awm.gov.au/people/roll-search/nominal_rolls/first_world_war_embarkation/. Return to text